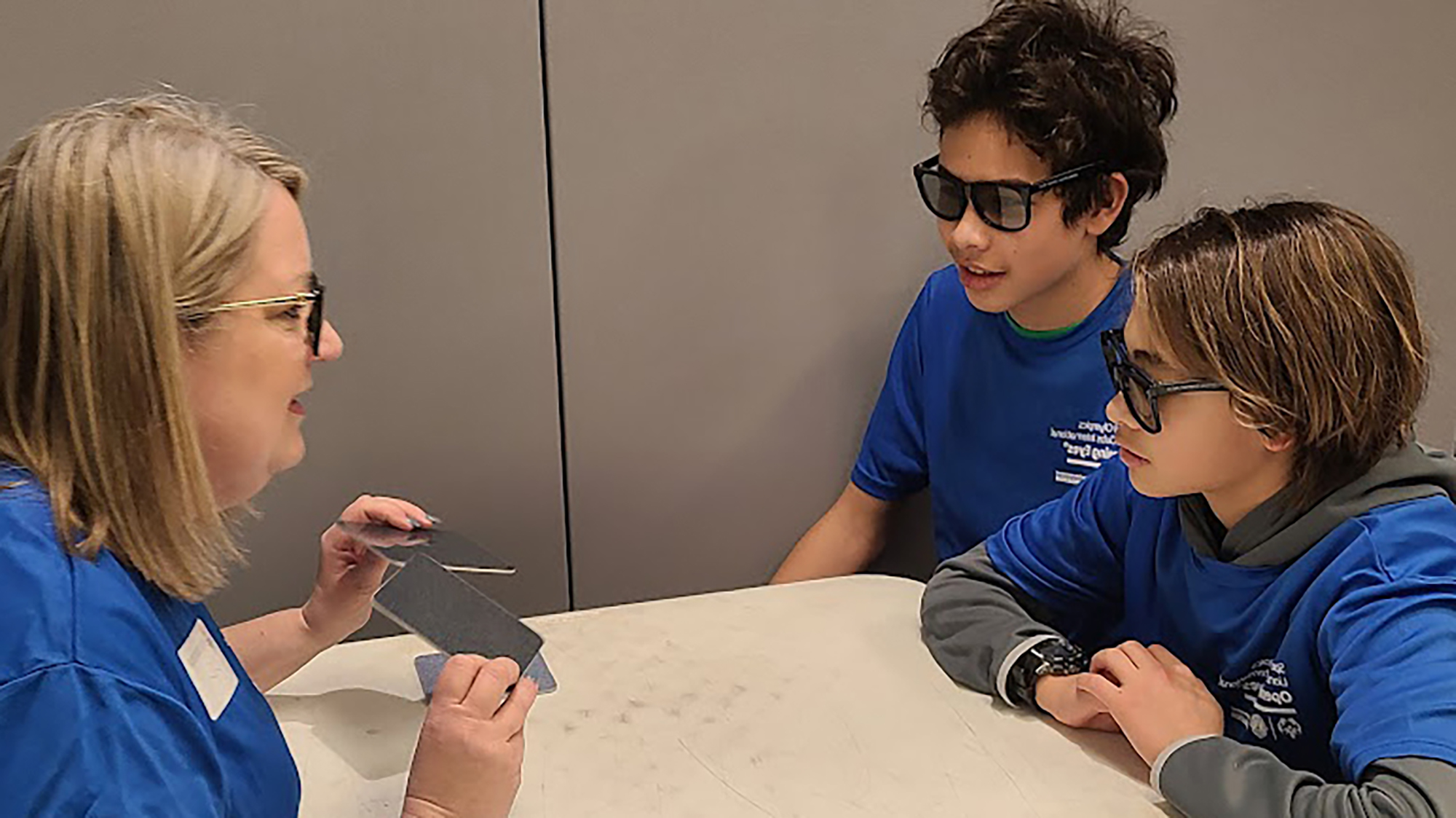

On January 27, Ping Moore, OD, was a part of an 18-person team of health care volunteers that traveled to Cartersville, Georgia for the Special Olympics’ Winter Games. There, they screened 54 athletes for glasses and eye diseases through Opening Eyes, a branch of the Healthy Athletes department of the Special Olympics.

On top of her full-time job at the Emory Eye Center, this volunteering gig took a significant chunk of Moore’s free time. But Moore doesn’t see it that way. She’s been volunteering for the group for more than 12 years, most recently as the clinic director for eye screenings. She wouldn't think of foregoing the chance to join in.

“I love seeing the athletes' determination,” she said.

“I'm humbled that some of the athletes have to work two-to-three times harder to achieve their goals in competition than those without disability. I love seeing the medals they earn and wear with pride from the events.”

Moore is now focusing on May 25, 2024, when Georgia's Special Olympics Summer Games will be held at the Emory University Atlanta campus. She is putting out the call for volunteers among her professional peers at the Eye Center. But she’s hoping her call will be heard beyond that, to anyone who has some compassion to lend.

“We’re looking for eye care providers and technicians, certainly, but there are tasks that anyone can perform. And we need people to fill those slots,” she said.

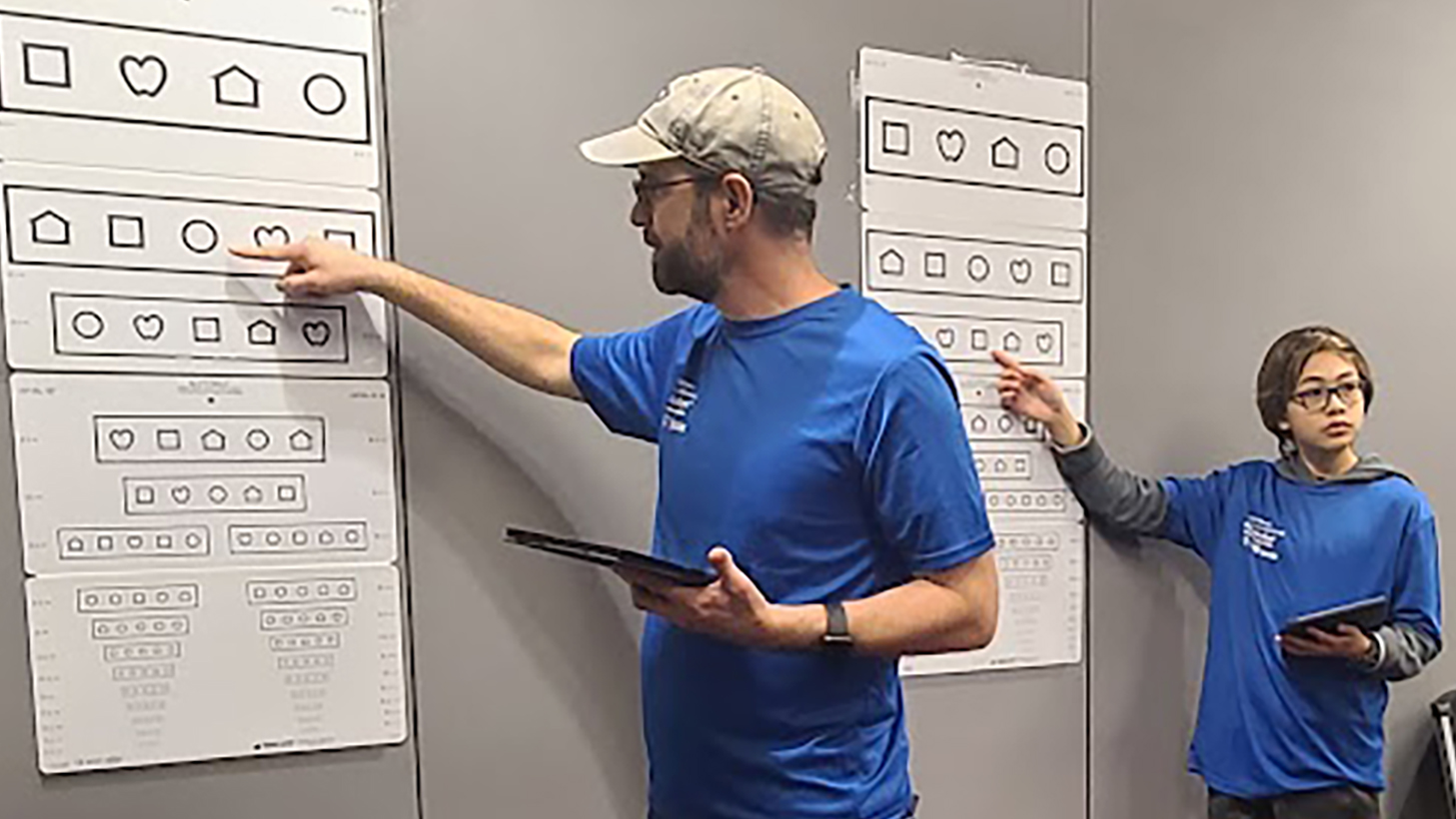

In Moore’s case, volunteer recruitment starts with her family. At the most recent Winter Games, her husband, Eric Moore, and two teenaged sons, Cillian, 12, and Isaac, 14, came along to help out. While Eric ran interference on IT issues between stations, the two boys were trained to help in a number of ancillary tasks.

“If any of my colleagues are wondering, they should just recruit their spouses and their children,” Moore said. “They will walk away feeling grateful for the experience.”

The Moores’ two teenaged sons can attest to that claim.

“My 14-year-old, Isaac, struck up a conversation with one of the athletes, who told him that when she was little, she used to play basketball with another kid regularly. But when that other child found out that this young athlete had an intellectual disability [ID], they stopped playing basketball with her. At that point, the athlete with ID started practicing by herself,” Moore said.

“As sad as this is, the athlete’s determination is inspiring. She kept going. And the lesson she imparted to Isaac about empathy was profound. I want my son to feel comfortable, to develop empathy when he encounters individuals who have ID [intellectual disability]. I do not want him to ever shy away. And the encounter he had with this athlete told him everything about why.”

-Kathleen E. Moore