Linear probe is best. However, the curvilinear (abdominal) probe may also be used in the obese patient. This is a static technique; pre-procedural skin markings are made using ultrasound guidance to guide the blind procedure. It is important to perform ultrasound markings in the proper lumbar puncture position and only when you are ready to start the procedure, as patient movements after the markings will decrease procedural success.

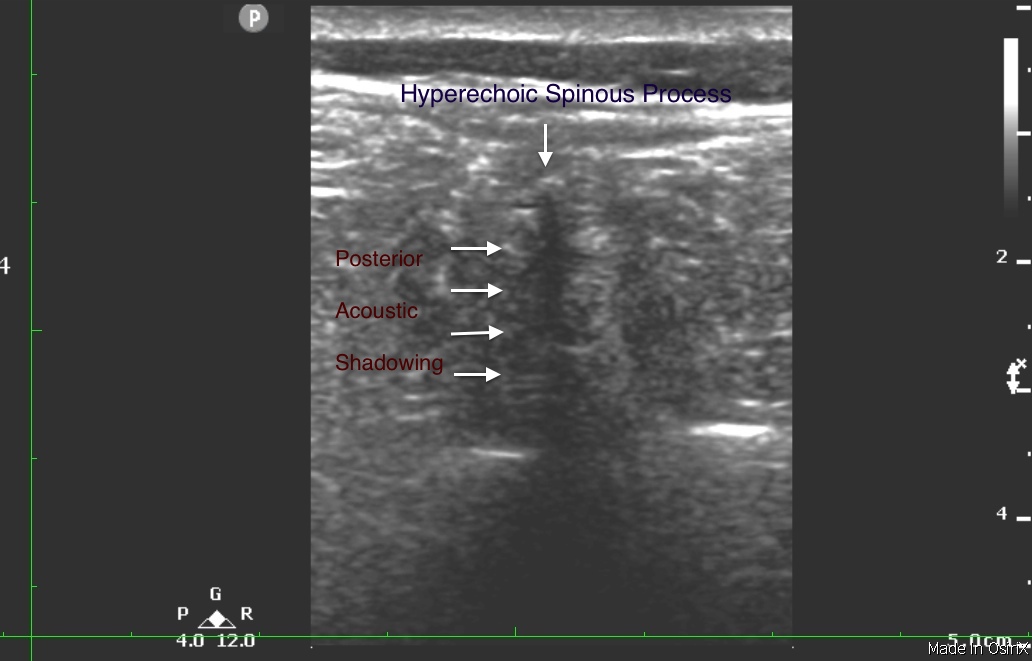

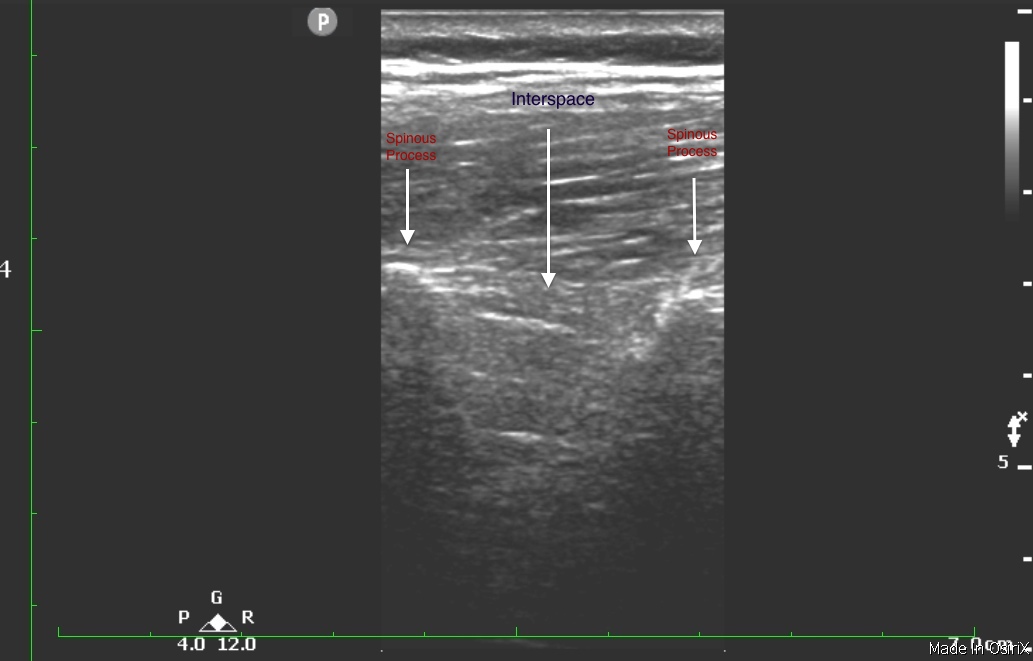

The technique is simply two-fold: 1) find midline and 2) find interspace. To identify midline start by placing the probe horizontally along the interspace at or above the anterior superior iliac spine. Midline is identified by the spinous process visualization on the screen as a hyperechoic (bright) structure with shadowing posterior. Center the spinous process on the screen and then draw a line with a sterile marking pen above and below the probe. Next, identify the spinous process by placing the transducer vertically along the spinous process you just identified. You will again notice hyperechoic spinous processes on the screen, this time up and down the screen. The interspace is the anechoic (black) space between two spinous processes. Center the interspace on the screen, and again mark to the left and right of the transducer on the patient’s skin. Now, you should have two lines drawn on the patient’s skin and where they intersect is the best spot for needle entry.

Image 1: Midline Still Photo

Image 2: Interspace Still

Clinical Importance: In an ever-increasing obese population, it has become challenging to perform lumbar puncture when landmark palpation is difficult. On the other hand, lumbar puncture indications such as subarachnoid hemorrhage, meningitis, and idiopathic intracranial hypertension are at times unstable for radiological fluoroscopic guidance. Therefore, it is imperative that the ED physician learns techniques to optimize success in the obese patient.

Results: Successful identification of pertinent structures (L4-L5 spinous processes and the spinal canal) occurred in 100% of patients with normal BMI, 95% of those who were overweight, and 74% of those who were obese (P = .011). Difficulty in palpating landmarks was noted in 5% of patients with normal BMI, 33% of those who were overweight, and 68% of those who were obese (P < .0001). In subjects with difficult-to-palpate landmarks, US identified pertinent structures in 16 of 21 (76%; 95% confidence interval, 53-92). The average distance from skin to ligamentum flavum was 44 mm in those with normal BMI, 51 mm in those who were overweight, and 64 mm in those who were obese (P < .00001); measurements between spinous processes did not vary by BMI. Overall, there was a moderate correlation (0.62) between BMI and the distance from skin to ligamentum flavum.

Conclusion: The usefulness of US in identifying structures for LP is inversely related to BMI. Even with this limitation, US is still able to identify obese patients' pertinent landmarks almost 75% of the time. In addition, US may be helpful in identifying pertinent structures for LP in those patients with difficult-to-palpate landmarks. In patients who were obese with structures not palpable by hand or identifiable by US, other modalities should be considered.

Image credit: Jobria Clendenin